(Only available through Soul Jazz records and outets)

How the world tuned into Jamaica: The sounds of Kingston’s dancehall craze revolutionized music and shaped the hits we listen to today

~ Rob Nash, The Sunday Times, UK, November 2, 2008

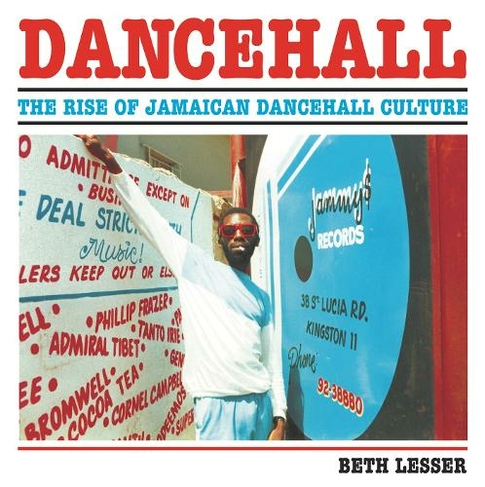

Sly and Robbie lean ostentatiously against the wall of a small studio in a dusty street. Nearby, in the middle of the road, reggae star Eek-a-Mouse smiles for the camera, wearing a trademark waistcoat-and-bow-tie get-up in red, green and gold. In Chancery Lane, a young Gregory Isaacs holds a plastic cup while someone fills it from a beer bottle. Chancery Lane, Kingston, that is. The photographs in Beth Lesser’s new coffee-table book, Dancehall: The Rise of Jamaican Dancehall Culture, depict a society so obsessed by music and so suffused with a can-do, DIY spirit that its disproportionate presence on the world stage seems inevitable.

Lesser first visited Kingston in 1981 as a wide-eyed 28-year-old Canadian reggae fan. She found the big new thing, the scene everyone wanted to be involved in, was dancehall. “You wouldn’t have known this was going on,” Lesser says, “looking at Jamaica from the perspective of Canada or the US, but when we got there, it was so huge you couldn’t possibly avoid it.” She spent most of the decade travelling to Jamaica and back.

“Until you go to the live dances, you can’t imagine what it’s like,” she continues. “You never knew what would happen. I remember the dance in 1985 when [the producer] King Jammy was playing the Sleng Teng versions, and just when it was getting exciting the police came, looking for guns, and closed it down.” There was one night even more memorable than that, though. “My husband and I got married at a dance,” Lesser says. “[The DJ] Major Stitch played the Michael Prophet record Here Comes the Bride.”

The 1980s are seen as the golden age of dancehall, when the serious political messages of Rastafarianism gave way to a boisterous music that drew the whole community into the party. At sound clashes, rival sound systems would unleash their most powerful weapons against each other: the latest dubplates (one-off pressings of tunes), the most experienced selectors (who choose the records) and perhaps a hot new DJ (who talks over it) with a fine line in bawdy patter.

Though in earlier times the two roles of selector and DJ were taken by one man, in dancehall the DJ was a vocalist, who would talk over the gaps between songs and also over the instrumental sections of the records, like a prototype rapper.

Lesser found the people who were making this music more than willing to be photographed as soon as they saw “a white woman with a camera”. Even established artists were welcoming. “What made a big impression on my first visit was that everything was so accessible,” she recalls. “You could go down on Orange Street, go to Pablo’s record store [Augustus Pablo, the acclaimed producer], and they’d say, ‘Pablo will be around soon’, then he would come in and chat. It wasn’t like you had to go through his secretary and make an appointment.”

In some ways it was amazing that people got anything done. The unavoidable marijuana question brings incredulous laughter from Lesser. “It was unbelievable,” she says. “In [the producer] Sugar Minott’s yard, they’d wake up in the morning and light up the chalice, and everyone would disappear in a huge puff of smoke. Wherever you went, everybody was smoking all day long.”

Kingston had a friendly atmosphere but there was an edge of danger. One day she and her husband were in a cab and another driver committed a minor infringement. “They were yelling at each other, then the cab driver pulls out a gun,” she says. “The other guy drove off and the cab driver put away the gun and said, ‘It’s okay, I’m a police officer.’ “

Political tensions were still high after the troubles of the 1980 election, and you had to be careful what colours you wore in certain areas. Black and red meant you were a socialist; if you wore green, you were a Labourite. In the exhaustive history that accompanies Lesser’s evocative photos, she paints a vivid picture of a scene that, despite its eventual global influence, was almost comically parochial at times. Its contained nature was also one of its strengths, as new ideas would develop rapidly. Lesser recounts a long-running gag about bicycle wheelies: “Early B had the one-wheel wheelie, the bicycle with one wheel in the air; then Chaplin came along with the four-wheel wheelie; and then somebody came with a lyric saying, ‘Four-wheel wheelie? There’s no such thing – you’d be flying.’ And then [the DJ] Junior Reid finally came along with Poor Man Transportation, saying he just walks everywhere .”

No doubt if you played the song Under Me Sleng Teng now, it would sound cranky; but the Sleng Teng rhythm was the first to be produced with synthetic instruments rather than a band, and it blew away the opposing sound system when King Jammy unleashed it at a sound clash in 1985. It was recycled hundreds of times. Two tracks on the Dancehall album use it, and when you hear them, it is quite obvious that a small Casio keyboard was the beginning and end of the technology behind them. With a little imagination, though, you can take yourself back 20 years to a warm night in Kingston and a revolution that ranks among the most exciting moments in popular music – the constabulary allowing.